Why booming AI coding apps may struggle to survive—and why infrastructure could be the real winner.

AI coding has exploded into one of the fastest-growing categories in the AI ecosystem. Products like Cursor, Claude Code, Lovable, and Replit are scaling at breakneck speed, with valuations and ARR numbers rising just as quickly.

However, behind the headline growth, deep structural flaws are beginning to emerge.

While some players project billion-dollar run rates, most remain unprofitable, constrained by skyrocketing compute costs and fragile business models.

As investors chase the next breakout, the real winners may not be the flashy coding assistants at all—but the quieter infrastructure platforms that enable them.

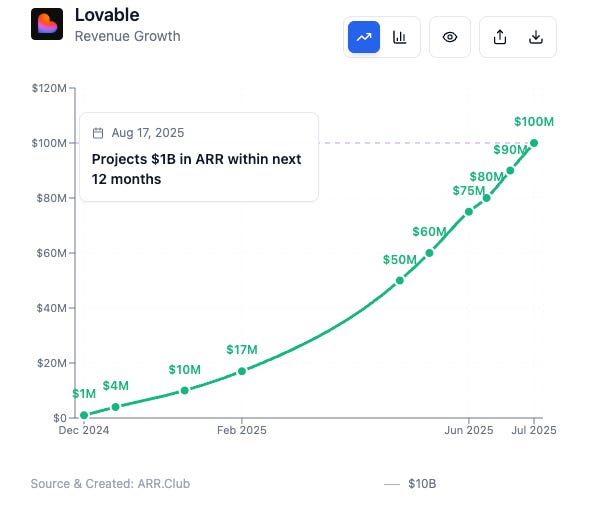

Last week, Lovable founder Anton Osika told Bloomberg that the company is adding $8 million in new ARR each month. He projects ARR will reach $250 million by the end of 2025, and could cross the $1 billion mark within the next 12 months.

But the surge has also exposed structural weaknesses: very few of these products are actually profitable.

Replit CEO Amjad Masad has admitted that the company’s old flat-rate pricing model was unsustainable, leading to periods of negative profitability.

After shifting to usage-based pricing, Replit’s gross margin now sits around 23%, and the company is focusing on large enterprise accounts where margins can approach 80%.

Cursor and Windsurf face similar dynamics, with heavy users pushing margins as low as –300% to –500%. Nicholas Charriere, founder of Mocha, has gone so far as to say that nearly all AI coding products run at zero or negative margin.

One potential solution is building proprietary models, but this path is prohibitively expensive. Windsurf reportedly considered it before abandoning the idea—possibly one reason it ultimately agreed to be acquired.

This brings to light a deeper issue: many of these products have not yet achieved what Chris Paik of Pace Capital calls “Business-model–product fit” (BMPF).

In his widely discussed essay Cursor’s Problem, Paik argues that while founders love to talk about product–market fit (PMF), they often overlook BMPF: the ability to sustainably extract value at a level proportionate to the cost of delivering it.

Cursor relied on a subscription model with “unlimited” usage, essentially fixing revenue while leaving costs variable.

Without actuarial discipline in pricing and segmentation, such models often collapse into what Paik calls the “MoviePass problem”: cohorts invert (the most profitable users churn, leaving behind loss-making ones) and topline revenue growth masks deteriorating unit economics.

Paik distinguishes between marketing and subsidies—both costly growth levers, but with very different effects. Marketing buys attention. Subsidies buy behavior, artificially inflating perceived product value. That illusion of PMF, he argues, is fragile; it disappears once true costs are revealed.

In the case of Cursor, margins are capped by dependence on frontier LLM providers like OpenAI and Anthropic. Downgrading to cheaper models risks user churn; sticking with premium models means variable costs can spiral out of control.

Cursor has already been forced to raise prices and add usage caps, frustrating users. As Paik puts it, until consumption is priced against cost, it’s impossible to know whether demand is for the product itself—or simply for the subsidy.

The broader takeaway: subsidies are not business models. They can act as a temporary bridge to defensible moats, but only if a clear path to profitable unit economics exists. Without BMPF, PMF alone cannot sustain a business.

Paik also highlights the fragility of “wrapper” strategies. Wrapping commodity infrastructure, as Snowflake did across AWS, Azure, and Google, gives leverage over vendors.

Wrapping a monopoly, by contrast, makes you a tenant, subject to rent extraction by the underlying platform. In the context of AI coding, products deeply tied to cutting-edge LLMs risk being squeezed if those costs don’t decline in step with usage growth.

While AI coding apps battle these challenges, the infrastructure layer between models and applications may ultimately prove the bigger winner.

Several platforms in this middle tier are growing just as explosively, but with far stronger margins—some as high as 76%. Vercel is reportedly raising at a $9 billion valuation, triple its $3 billion valuation just a year ago.

Notable examples include:

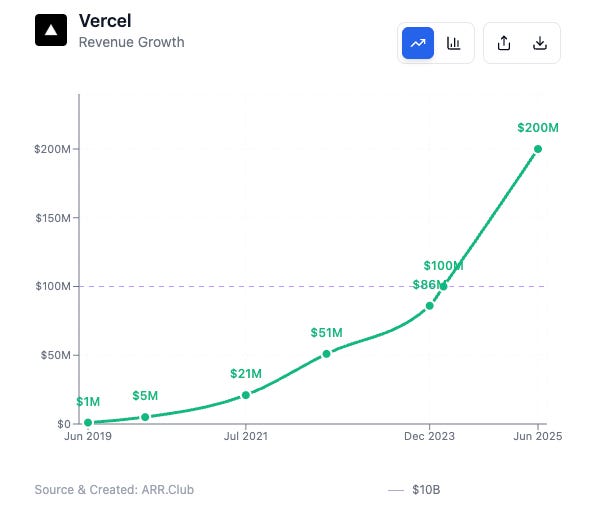

Vercel, which simplifies building and deploying modern web applications. It surpassed $100M ARR in March 2023 and $200M in June 2024.

The company is reportedly in talks for funding at a $9B valuation, up from $3.25B last year. Gross margins stand at 76%.

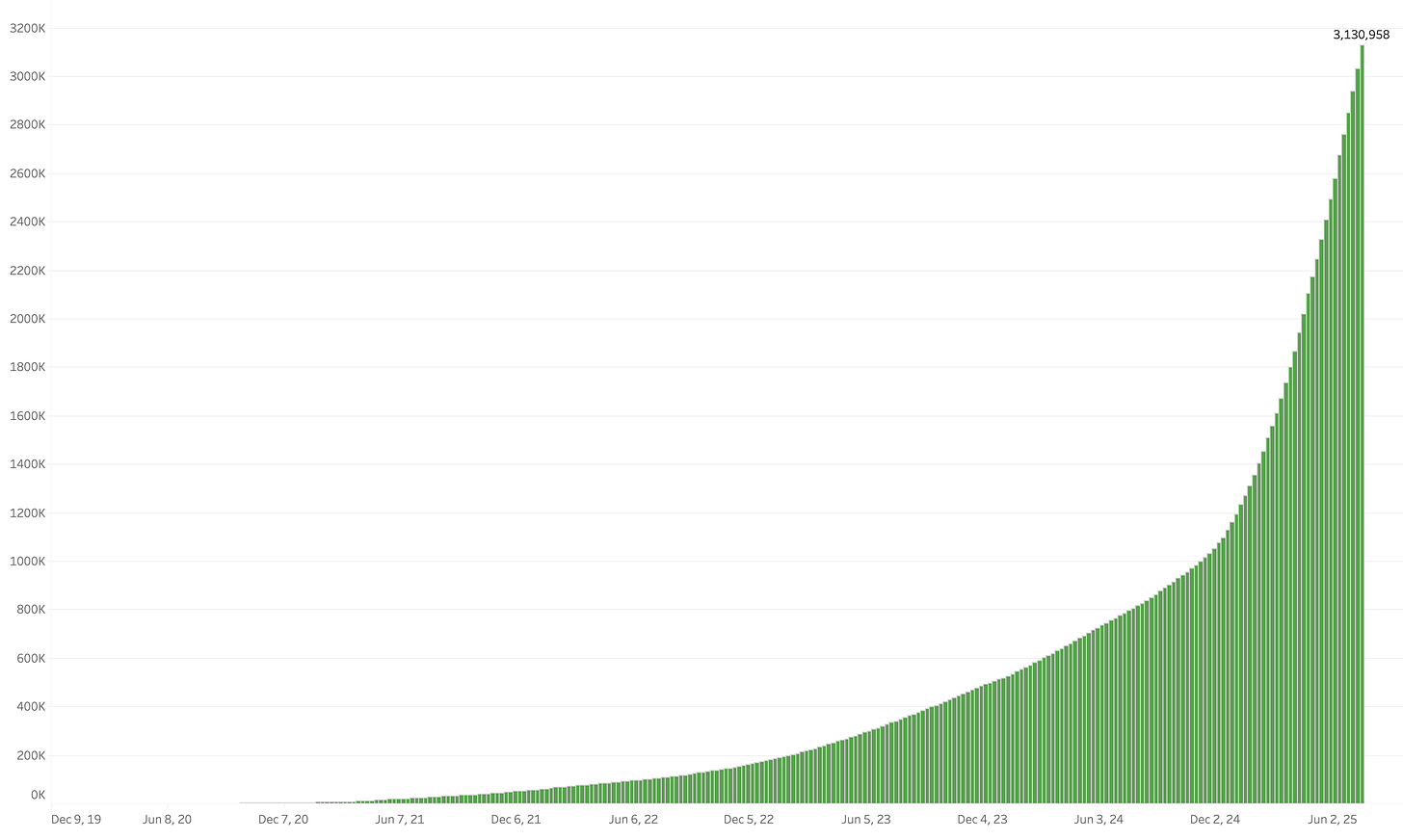

Supabase, often compared to Heroku, has become a foundational piece of the AI coding stack.

Its developer base grew from 1M to 2M in four months, then to 3M just three months later. Nearly every “vibe coding” product leverages it as part of their GTM motion.

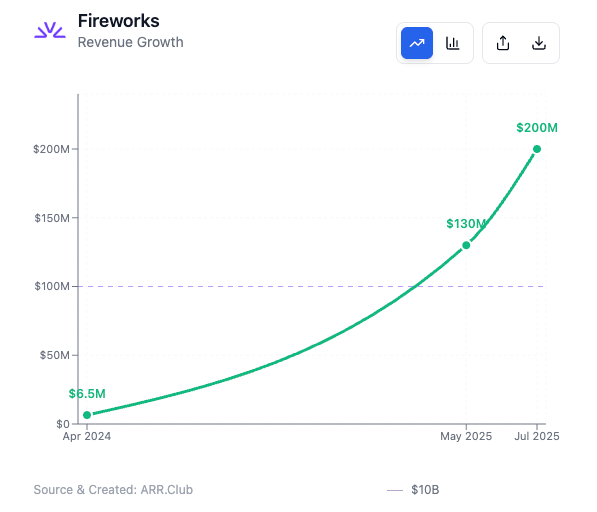

Fireworks, positioned as a GenAI platform-as-a-service, crossed $130M ARR in May 2025, hit $200M by July, and is projected to surpass $300M by year-end.

Fal, a generative media platform, grew from $1M ARR last year to $40M earlier this year, and has since reached $55M with a net dollar retention of 400%.

Following a $125M Series C at a $1.5B valuation, the company now serves over 2 million developers and 300+ enterprise customers.

While the long-term profitability of AI coding apps remains uncertain, the infrastructure providers powering them—Vercel, Supabase, Fireworks, Fal—appear far better positioned to capture sustainable value.